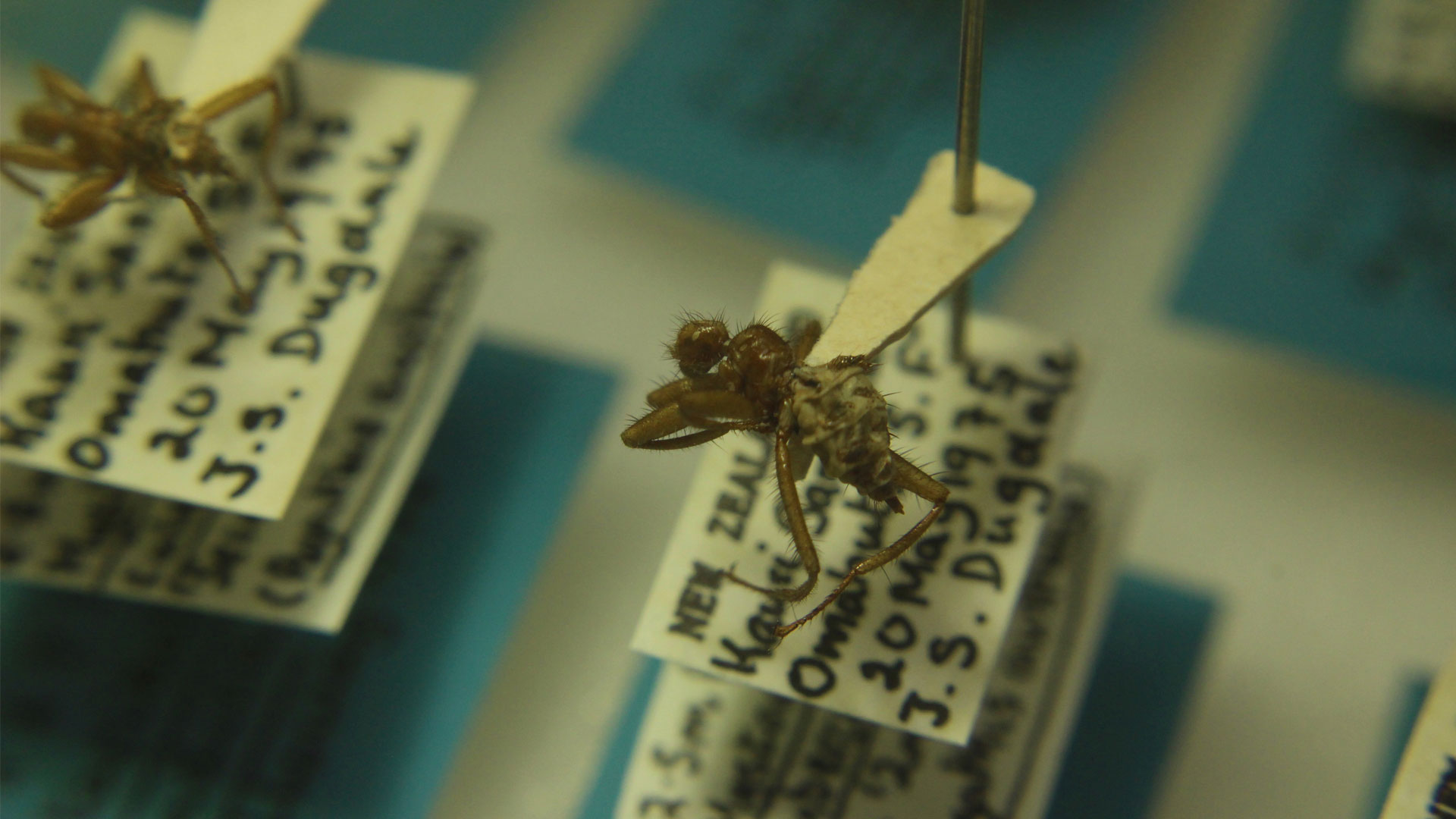

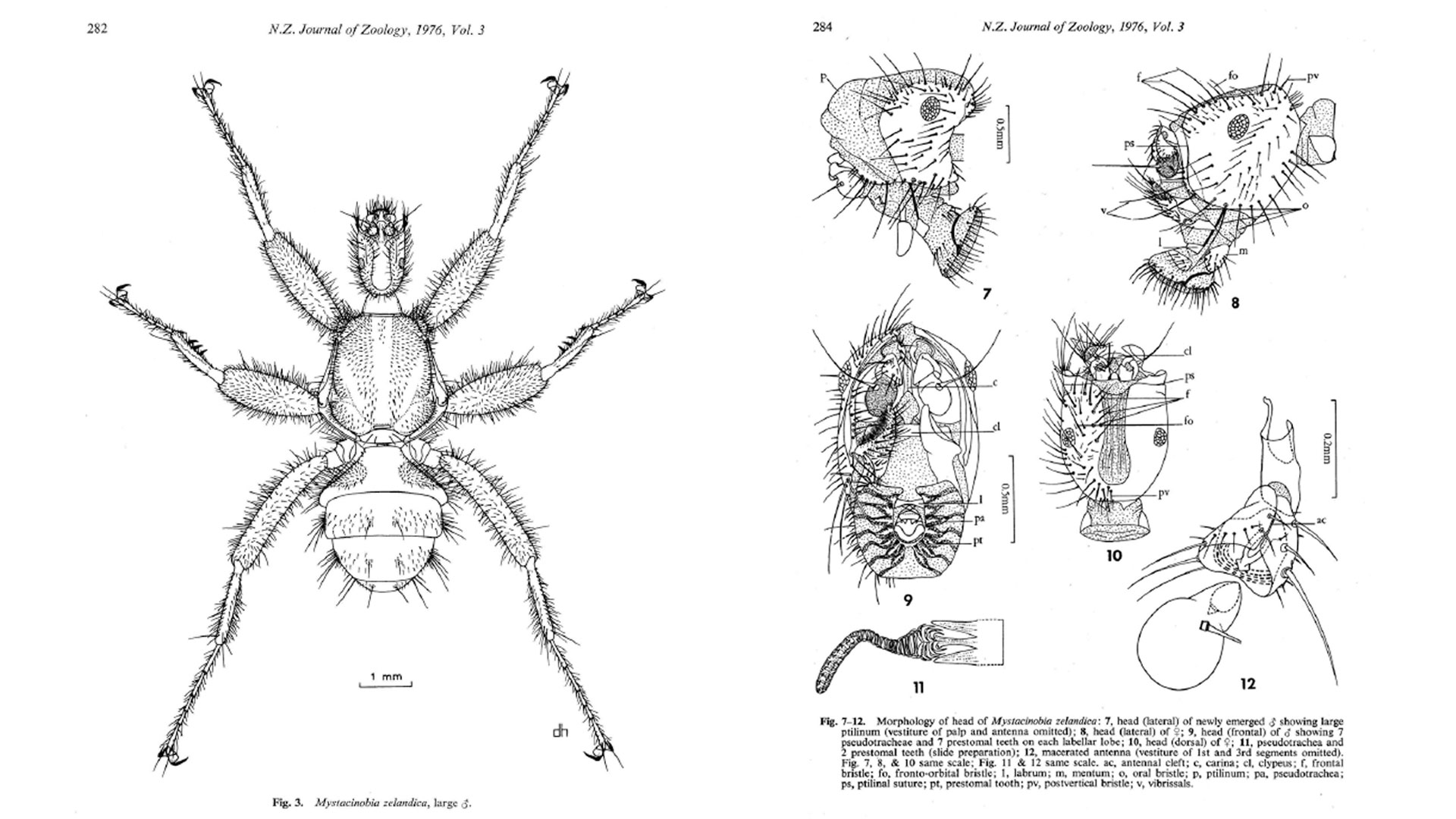

Dr Holloway found that the New Zealand bat-fly was not a parasitic bloodsucker, but in fact a coprophage (poo-eater) and did not have the modified mouthparts required for piercing skin. Not being able to fly itself, the New Zealand bat-fly has claws adapted for movement over fur, which they can also use to catch a ride outside the roost! Gravid females (those carrying fertile eggs) will accompany bats on their nocturnal feeding expeditions with a clever evolutionary purpose. Should this bat decide to relocate and not return to its original roost, a new colony of bat-flies can be set up at a new location.

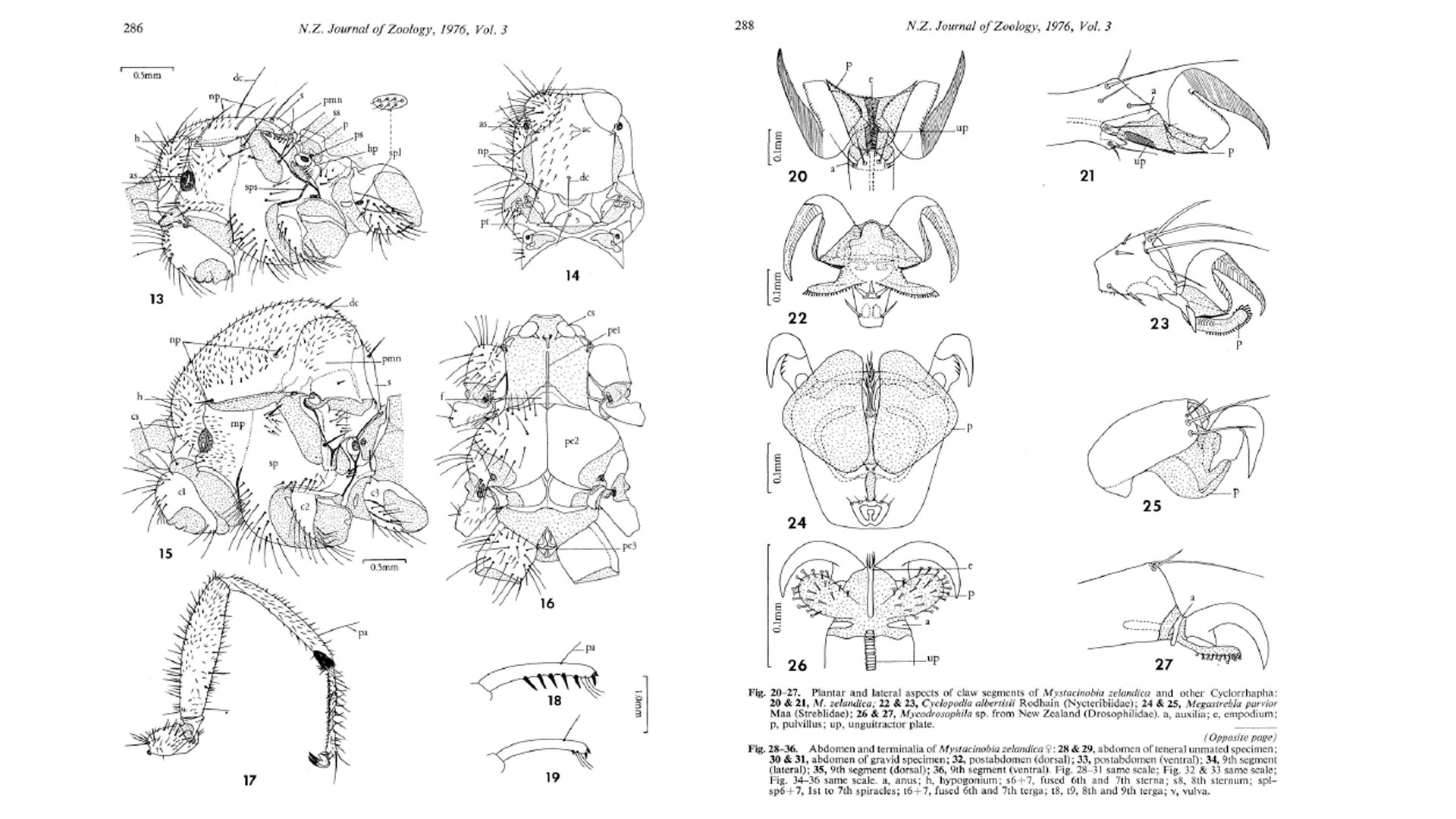

“The need for unusually high temperatures and a yeasty diet combined with the loss of flight has resulted in the flies becoming totally dependent on the bats… The total dependence of Mystacinobia [the bat-fly] on Mystacina [the short-tailed bat] for food, shelter, and dispersal suggests a very long association between the two, perhaps predating the arrival of their ancestors in New Zealand.” – Dr Beverly Holloway, 1976

In order to share a co-dependent life with an insect-eating bat these flies have evolved extreme specialisations; males are capable of creating high, shrill sounds which are thought to cause some discomfort to the bats and prevent predation – which is key when you’re sharing the same home. In winter when entire bat colonies enter a state of torpor, and the temperature within the colony drops, the bat-fly larvae are able to slow their development, waiting until the bats become active again and temperatures increase before continuing on with their life-cycle. Perhaps the most unusual adaptation of the New Zealand bat-fly is their social interactions. Bat-fly generations overlap, meaning that the adult flies live with and amongst their own progeny. Adult flies and larvae are also known to mutually groom each other – a behavior most often associated with primates, not flies.

This video from Te Ara shows a female fly depositing her eggs close to a newborn bat. When the eggs hatch, the batfly larvae are then able to attach themselves to the baby bat’s skin.